If you have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), this scenario might sound familiar: you have a looming, mundane task ahead of you that requires sustained focus and energy. Although you are fully aware that you have this task to complete, an insidious feeling of inertia creeps in each time you think about working on it. You simply cannot motivate yourself to get started until the task is absolutely urgent. As such, you tend to find yourself stuck in a cycle of stressfully scrambling to finish things at the last minute.

To an outside observer, this cycle might be wrongfully viewed as a product of laziness or carelessness. Yet in reality, people with ADHD tend to be highly ambitious and goal-driven. However, the neurological differences in the ADHD brain can make it very difficult to organize for the future and carry out goals to completion. In other words, ADHD creates problems with motivation and performance. As one individual with ADHD eloquently explained, “It’s as if there is a disconnect between the part of my brain that is conscious of the task and the part of my brain responsible for actually executing the task.” Although this individual’s explanation is anecdotal, advancements in neuroscience have demonstrated some truth behind their claim.

What Neurological Factors Impact Motivation in ADHD?

Executive Dysfunction

The primary symptoms of ADHD as defined by the DSM-5 are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. However, recent neuroscience research has determined that ADHD is primarily a disorder of executive functioning. Located in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, executive functions are higher-order cognitive processes that help us perform goal-directed behaviors – e.g. planning, organizing, self-monitoring, time management, filtering out distractions, and more. They are responsible for prioritizing important things in our environment and orienting our attention and behavior towards those things. According to ADHD expert Dr. Russell Barkley, executive dysfunction impacts over 90% of individuals with ADHD.

Deficits in executive functioning create a discrepancy between the intention to engage in a behavior and actually engaging in that behavior. This intention-behavior gap poses a fundamental challenge: it makes it difficult to organize present behaviors across time to achieve a larger future result. The consequence is that people with ADHD tend to have a hard time getting motivated to do the things they know they need to do. For instance, an individual with ADHD may often intend to begin a work task a week before the deadline, yet chronically fail to get started until the day before. Such problems with motivation can seriously impede social, occupational, and other areas of daily life.

Working Memory

Executive functioning is responsible for a host of performance-related tasks, but it is reliant on an underlying brain system called working memory. Working memory allows us to hold and manipulate incoming information in our minds in real-time. Acting as a mental scratchpad, working memory juggles multiple pieces of information at once so that they can be used simultaneously to carry out an action. However, those with ADHD have less bandwidth in their working memories than neurotypical people – there is significantly less space on their mental scratchpad. As such, people with ADHD have trouble keeping in mind multiple priorities of varying interest at any given time. The present moment tends to win out over delayed outcomes of greater value, which often leads to procrastination and task paralysis.

Take the work scenario above for example: although the deadline is a week away, a neurotypical person can successfully engage their working memory to bring all the information associated with the task online. When they think about the task, they juggle a variety of different memories in their mind: how many smaller steps are involved in the task, the date of the deadline, the amount of time it took them to complete the task last month, and so on. They are then able to consider all of this information together to create a realistic timeline for the task’s completion – this in turn incites the motivation to act.

However, working memory impairments in ADHD make it very difficult to take the bigger picture into account. It’s as if people with ADHD are watching the world through a telescope, unable to accurately visualize the threats or opportunities outside of their current field of view. In the example above, the looming work deadline exists outside the lens of the telescope and the “now” takes precedence. Thus, the information being received in the present feels much more motivating and compelling than vague memories associated with the future.

Dopamine Deficiencies and Reward Pathways

In addition to these structural differences, ADHD has been shown to affect the release of motivation-related neurotransmitters, namely dopamine. Neurotransmitters are the chemical messengers in our brains. Their jobs are to transmit signals between brain cells in order to regulate our bodily functions.

Dopamine is one neurotransmitter that plays a key role in our motivational and reward systems. It fuels our passion for possible rewards in the future, which prompts the pursuit of those rewards in the present. After we have successfully achieved a goal, the dopamine system provides us with positive reinforcement: a warm feeling of pleasure or satisfaction. Memories of these positive feelings then cause us to seek out more opportunities for rewards later on, hence driving our motivation. A balanced dopamine system helps us easily move between states of motivation, relaxation, focus, and rest. But what happens when the dopamine system is unbalanced?

According to current research, ADHD appears to be associated with low levels of dopamine in the brain. Dopamine deficiencies in ADHD make it very difficult to derive reward from ordinary activities. For instance, imagine you have just finished dinner and you now have two things on your mind: your desire to watch your new favorite TV show and the fact that the kitchen needs to be cleaned. Obviously, one option sounds significantly more appealing than the other. Yet, a neurotypical person can usually garner the motivation to choose the mundane task first. The anticipation of a pleasurable dopamine rush that will come after finishing the chore unconsciously motivates them to act.

Unlike neurotypical people, however, individuals with ADHD cannot count on this subsequent surge in dopamine. Since dopamine is less available, they require much stronger incentives to trigger a dopamine release large enough be motivating. As such, ADHD brains crave stimuli that are highly interesting and provide immediate rewards – i.e. watching a new show on TV. The long-term gratification of keeping the kitchen clean simply cannot compete with the short-term pleasure of watching exciting TV.

Additionally, low dopamine in people with ADHD creates endless incentive for high-reward seeking behavior. The human brain is designed to pursue chemical balance, but the ADHD brain challenges this pursuit. Since it exists in a dopamine deficit, the ADHD brain is in constant search of stimulation that will quickly restore dopamine to baseline levels. The consequence is that people with ADHD tend to seek out situations that are high-risk, high-reward – for example, gambling, binge eating, driving fast, over-spending, or using drugs. While a neurotypical person might describe a “rush” they feel after engaging in these behaviors, people with ADHD often report feeling more focused and calm. Although it sounds contradictory, the rapid spike in dopamine actually stabilizes the normally dysregulated ADHD reward system. Thus, the pursuit of highly pleasurable rewards can become a powerful, albeit flawed, form of self-medication for ADHD.

How Can Problems With Motivation Affect Mental Health?

Problems with motivation can have major consequences for one’s wellbeing. Living in a constant state of procrastination is both psychologically and physically taxing on the body. Indeed, the stress that accompanies last minute scrambling can initiate the body’s fight-or-flight response, also known as the acute stress response. This state of high alert can be useful at times because prepares the body for action and motivates behavior. However, long periods of high stress can wear the body down and create a neurotoxic environment in the brain. Furthermore, stress research has linked long-term stress to depression, insomnia, fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, headaches, and chronic illness.

Additionally, frequently failing to do the things you intend to can negatively impact self-esteem. ADHD tends to feel like an uphill battle. Despite the best intentions, executive functioning deficits make it hard to perform the necessary steps to achieve set out goals. This struggle can stunt confidence and lead one to develop negative self-beliefs – for instance, “I will never be good enough.” On top of this, the average person often conflates motivation problems in ADHD with a lack of willpower. Although ADHD has nothing to do with willpower, many people with ADHD still find themselves internalizing these misinformed criticisms. All of these factors can take a toll on mental health and one’s sense of self-worth.

How to Improve Motivation in ADHD: Solutions and Strategies

Although ADHD can create problems with motivation, there are many ways to change your habits, increase your motivation, and accomplish your goals. Try these tips:

Break down large tasks into smaller chunks

Having ADHD can make a large task seem impossible to tackle. Problems with executive functioning create barriers for planning and time management. Additionally, poor working memory makes it hard to hold multiple things in mind at once, which can further prevent you from getting started. A helpful way to simplify a looming task is to break it down into smaller steps or chunks. Also called scaffolding, this technique allows you to visualize something big and multifaceted as a simple sum of its parts. Breaking down a task reduces the stress and anxiety of starting a big project and instead prompts immediate action. To try this technique, you can simply use a pen and paper to list out all the steps of your task. However, if you’re having trouble identifying each step this fun online tool will do the work for you.

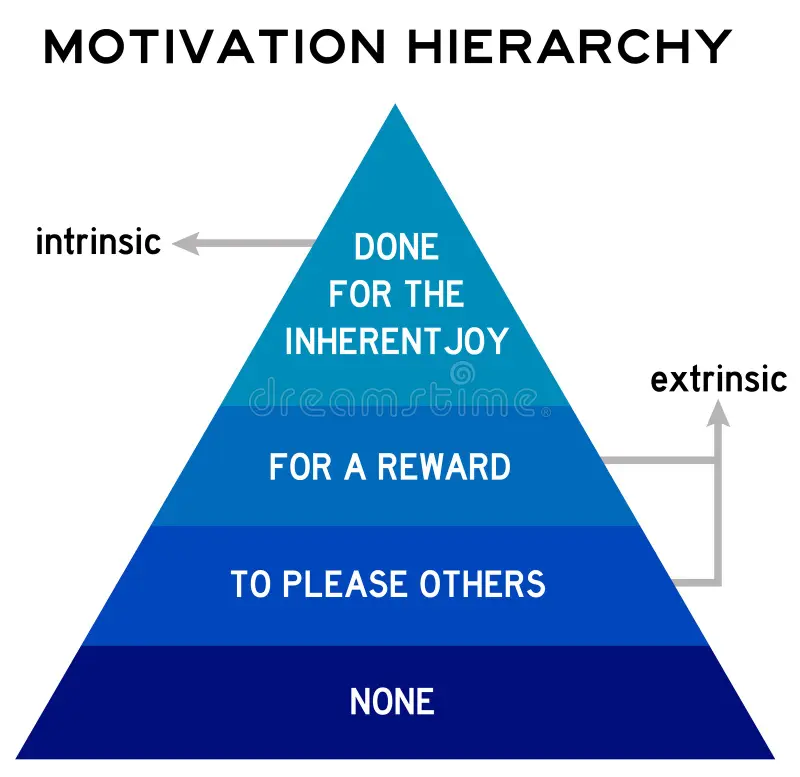

Create extrinsic rewards for yourself

As aforementioned, ADHD is associated with low dopamine the brain. Thus, people with ADHD cannot count on their internal reward pathways to motivate their behavior. Although dopamine may be an unreliable source of motivation, creating your own external reward system is an extremely useful way to make up for dopamine deficiencies. For example, imagine it is the beginning of the week and you notice your fridge is empty. Although you know it would be smart to go grocery shopping, the ease and instant gratification of ordering dinner sounds much better to your ADHD brain. But what if you could find a way to make grocery shopping instantly rewarding too? As a bonus for saving money on groceries, you could treat yourself to one specialty item at the supermarket each time you go. By rewarding yourself for finishing a mundane task, you incentivize the task, which in turn increases your motivation to complete it in the future.

Externalize your tasks and goals

Poor working memory in ADHD can make it difficult to remember your goals. When working memory becomes overloaded, important information is easily tossed aside and forgotten. This poses obvious challenges for motivation and task initiation. To reduce forgetfulness, get into the habit of immediately offloading ideas or tasks onto an external source. You can use To-Do lists, wall calendars, planners, sticky notes, or the “Notes” app in your phone. The key here is to find a method that works for you and stick with it. By externalizing your goals, you take the pressure off of your working memory and increase the likelihood of achieving all the things you’ve set out to do.

Use the Pomodoro Technique

The pomodoro technique is an ADHD-friendly method for improving productivity and focus. It involves structuring your work and break periods by specific increments of time: 25 minutes of work followed by a 5-minute break. This cycle is called a “pomodoro.” After 4 pomodoros, you can enjoy a longer 15-30 minute break. The pomodoro technique “gamifies” productivity by making it a race against time with built in rewards. The 25-minute intervals measure your focus on a singular task and instill a sense of urgency within that time frame. After the 25 minutes, you are immediately rewarded with a break. Thus, the pomodoro technique can turn a menial task into an opportunity for instant gratification and achievement.

Try Body Doubling

Body doubling involves working on a task alongside someone else. Acting as your “body double,” this person helps you hold yourself accountable and keeps you focused on the task at hand. Body doubles can be especially useful for long and tedious tasks that require sustained mental focus – for instance, re-organizing your closet or clearing out your filing cabinet. You can use a friend or family member as a body double or find someone virtually on an online body doubling platform. The simple presence of another person is sometimes enough to keep you from getting sidetracked or giving up.

Consider a fast paced career

There are many strategies that can help increase your motivation to complete long or uninteresting tasks. However, if you struggle to find motivation and enjoyment in life on the daily, you may want to consider adapting your lifestyle to accommodate your dopamine-seeking brain. Indeed, some people with ADHD are the most successful in high intensity careers (like those of ER doctors, firefighters, or crisis managers) because of the greater dopamine involvement in such roles. Finding a profession that satisfies your craving for stimulation can also reduce the likelihood of engaging in high-reward behaviors that are dangerous or destructive.

In Conclusion

The structure and function of the ADHD brain can negatively affect motivation. Differences in the prefrontal cortex cause deficits in executive functioning and working memory. Such deficits make it hard to plan for the future and take action towards goals. Additionally, low dopamine levels inhibit the ADHD brain’s reward pathways, which can lead to a lack of motivation for anything that does not provide immediate enjoyment. While these neurological differences are important to understand, individuals with ADHD do not have to surrender to them. With the right strategies and adjustments, those with ADHD can build habits that foster motivation and action.

Our team at the ATTN Center in NYC offers a variety of services to support you with ADHD symptoms. This includes therapy for ADHD-related anxiety and depression, group therapy, ADHD-focused therapy, testing, and neurofeedback options. At ATTN Center of NYC, we do everything in our power to treat ADHD without the use of medication, but we understand in some severe cases additional measures may be needed. As a result, we also maintain close relationships with many of NYC’s best psychiatrists as well. Feel free to learn more by visiting our blog or FAQ page today.